By Bryam R. Medina Matos

I grew up in the Dominican Republic and attended school there for twelve years. During that time the school used a grading system that was simple for all students to understand: 10% attendance, 10% participation, 30% process and effort, and 50% tests. Process and effort involved factors like attendance and completing the assigned work. So if a student was diligent, his grade was impacted in a positive way.

I moved to the United States two years ago, and the grading system is completely different than the one I was used to. Here, grading is based on the results—on test scores. It is a system that grades the student only on the outcome, not the process. Teachers and headmasters proclaim that if you are in school every single day, you will earn a better grade. But that’s not true for every student. Students with special challenges—like English Language Learners—may attend school every day and work just as hard, or harder, than a student who has English as his first language. But it may take longer for them to do the assignment because understanding what the text is saying or understanding the instructions for the assignment is more difficult. They have to think, revise and summarize in Spanish, and then translate it into English. Even though they are working extremely hard, it may not show in the result because of the language difficulty. So assessments based only on results of student work is not an accurate indication of the student’s intelligence, ability, or effort.

A student who focuses on the process of learning, who participates and interacts with fellow students, learns soft-skills like time-management, communication, cooperation and other social-emotional skills. If the jobs out there all require well-developed social and emotional skills, why are schools focused on the product without believing in the process? If we care about process in the real world, then we should care about it in school. For instance, someone working in a hardware store is always focusing on process. He has to show up for his shift and arrive on time; he has to get along with others; he has to be helpful to the customer. The “products” of working in a hardware store might be praise from the boss, a pay increase, and a feeling of self-satisfaction. School should function in a similar way. It is not right to evaluate students’ success or failure based on things over which they have no control, such as intelligence or life circumstances. When schools are focused only on test scores and attach students’ worth to the outcome, students become resistant to trying new things, taking risks, and putting forth their best effort—despite setbacks and mistakes. Making mistakes is essential to creativity and learning. When you define yourself by performance rather than your effort, you stop yourself dead at the starting gate.

According to Laura Gersch, a teacher at Margarita Muñiz Academy in Jamaica Plain, “The process is the product. By virtue of putting in effort, students are much more likely to be engaged and comprehend and retain the hard academic material.”[1] She says that if you are writing an essay and you spend lots of time revising (which is process work), you are going to end up with a better essay (which is the product), and you will be more invested in your work.

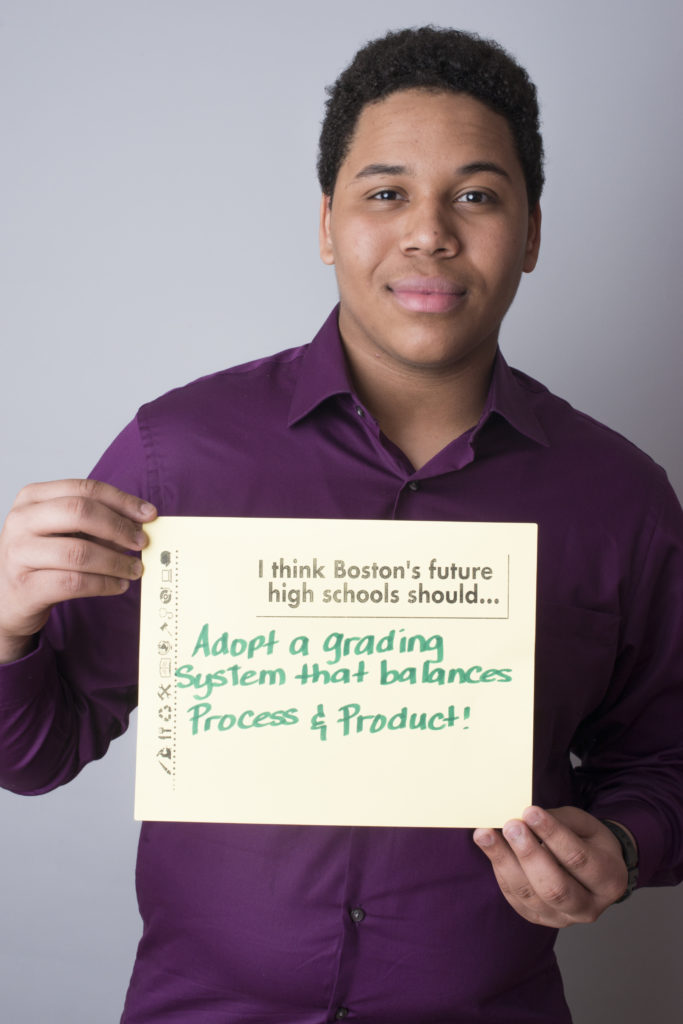

School should be designed to create human beings with good work habits, creative ideas, and problem-solving skills. A system that evaluates students on both product and process would increase the student’s effort and encourage them to keep working hard and to do everything that is required to pass the class . A 50/50 grading system that measures both process and product is good for learning and is a more accurate assessment of a student’s ability. It’s also easier for parents to understand. I think the Boston Public High Schools should consider adopting it.

- Laura Gersch (12th grade teacher, Margarita Muñiz Academy), in discussion with author, January 23, 2016. ↑

You must be logged in to post a comment.