By Jonatan López

When I first arrived to Boston from Puerto Rico I started second grade right away even though I didn’t know English. On my first day of school I was terrified. For the first assignment, the teacher made us write down the city we lived in, and then we went around and introduced ourselves. I stood up and said, “My name Jonathan. I live in Bo-ton.” I said it with my accent, making the class giggle.

Unfortunately, this experience is not unique. Dr. Dania Vasquez, principal of the Margarita Muniz Academy, became a bilingual educator 36 years ago and has been advocating for bilingual students ever since. She remembers when a professor recommended she spend an extra year in school to improve her Spanish accent to sound more like an American. Her classmate from Dallas also had a thick Southern accent, but wasn’t asked to stay in school. Dr. Vasquez believes that that every student should have the opportunity to bring all of themselves to school, including their culture. “Doesn’t matter who you are—Black, Latino, Asian, White—if you’re bringing a culture or another language to school, you should because it’s an asset. As a Latina, growing up I was told that being Latina was not an asset…but a problem.”[1]

As a newly arrived student at the Curley K-8 School, I felt left out because the monolingual students had their own hallway. However, Spanish speakers sat separately during lunch. And because our ESL classes were smaller, other students would tease us and call us dumb. Not only was I mastering my sixth grade lessons but I was one of the honor roll students who helped those who were struggling with English in the class. After two and a half months into my seventh grade year I was pulled out of my class and moved to the regular program. Not only did it make me feel nervous, but deep down I knew it was going to shift me off the road I was on. The school administration moved me that day. When I entered the class everybody stared at me as if I was a new student.

There are other Hispanic immigrants who get treated differently just because they aren’t able to speak English or communicate with others. This causes them to feel like outsiders. This not only causes them to lose interest in school but it also causes them to drop out more. In 2014 Hispanics between ages 16 and 24 had the highest dropout rate of any other minority group at 10.6 percent. By comparison, the white student dropout rate was only 5.2 percent.[2]

Not only did my grades start dropping when I started the regular program, but I was no longer an honors student. This made my enthusiasm for hard work go away. Adding to my frustration, some of the students in my new class spoke to each other in Spanish. I realized that I could’ve been placed in the English program sooner. It also took me a while to understand the new curriculum since we were learning different subjects in this new regular classroom.

I started at a brand new dual-language high school called Margarita Muñiz Academy in 2012. They had the help I didn’t receive in middle school or elementary school.

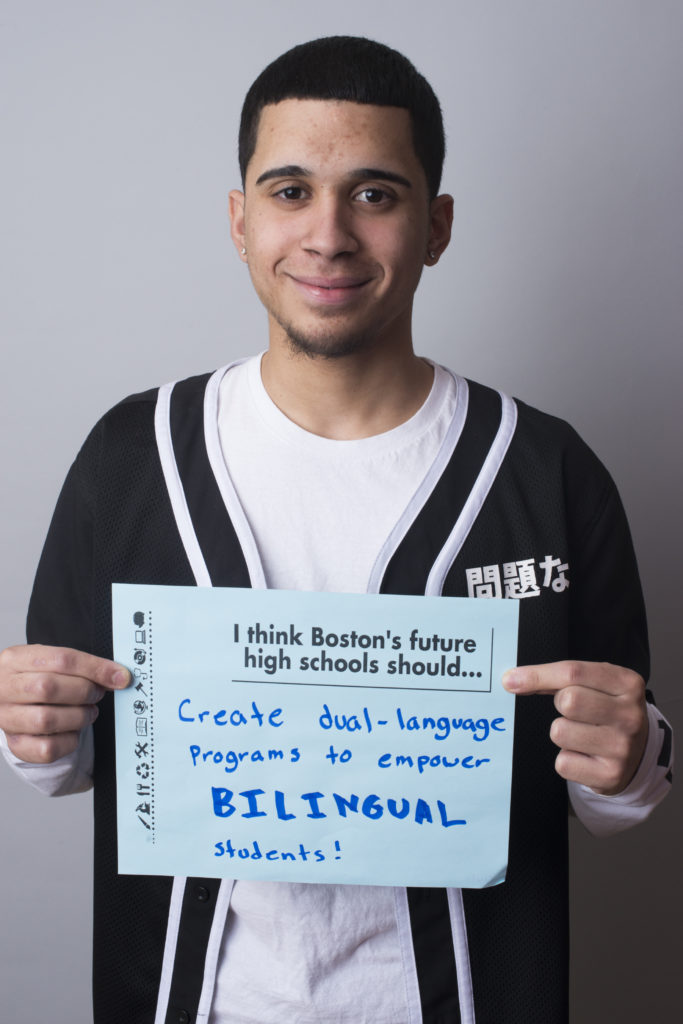

Schools need to have more dual-language programs so that the students that need extra help can at least get it. Also, putting bilingual students with regular students will help the environment because both sets of students will learn another language. This could make the community stronger since the students can help each other. Each student at each school should be able to take a subject in his original language. The point is to have monolingual students be fluent in Spanish and Latino students fluent in English. Not only will it benefit both, but it’ll open more doors and it’ll make students’ thinking stronger.

In 2004, Virginia Collier and Wayne Thomas published an eighteen-year study of dual- language programs in twenty-three school districts and fifteen states. They learned that “the effectiveness of dual-language education extends beyond academic outcomes. The entire school community benefits when multiple languages and cultural heritages are validated and respected. Friendship bridges class and language barriers. Teachers report higher level of job satisfaction. Parents from both language groups participate more actively in schools.”[3]

I actually got to witness all of this when I started at a brand new dual-language high school called Margarita Muñiz Academy in 2012. They had the help I didn’t receive in middle school or elementary school. They have teachers that advocate for students even when the students don’t care or feel like giving up. The teachers are focused on making everybody succeed. Not only did I see a lot of Spanish kids enroll but I have also seen an African-American student who spoke no Spanish enroll which made me think he wasn’t going to succeed in a bilingual school. After a couple of years he mastered the Spanish language and now he speaks Spanish. Many people were impressed. Seeing monolingual students trying to understand a different language and appreciating the help they got from bilingual teachers and students made me realize that we’re capable of sitting in the same classroom.

Elena Izquierdo, a professor of bilingual education at the University of Texas at El Paso, said “Dual-language takes longer, in part because so much time is devoted to Spanish grammar and literacy. But it pays off down the road. “Learning how Spanish works helps [students] develop the cognitive skills they need to learn English well.” “When it all clicks into place,” Izquierdo said, “it’s an amazing thing to see.”[4]

- Dr. Dania Vasquez, in discussion with author, January 26, 2016. ↑

- “High School Dropout Rates,” Child Trends Data Bank, November 2015, http://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=high-school-dropout-rates. ↑

- Melanie Smollin, “5 Reasons to Love Dual Language Immersion Programs,” TakePart.com, June 6 2011, accessed December 7, 2015, http://www.takepart.com/article/2011/06/06/5-reasons-love-dual-language-immersion-programs. ↑

- Nate Blakeslee, “Dream of a Common Language/Sueno De Un Idioma Comun: The Graduates of a Radical Bilingual Education Program at Alicia R. Chacon International, in El Paso, Would Have No Trouble Reading Either of These Headlines. What Can They Teach the Rest of Us about the Future of Texas,” Texas Monthly, September 2009, 108. ↑

You must be logged in to post a comment.