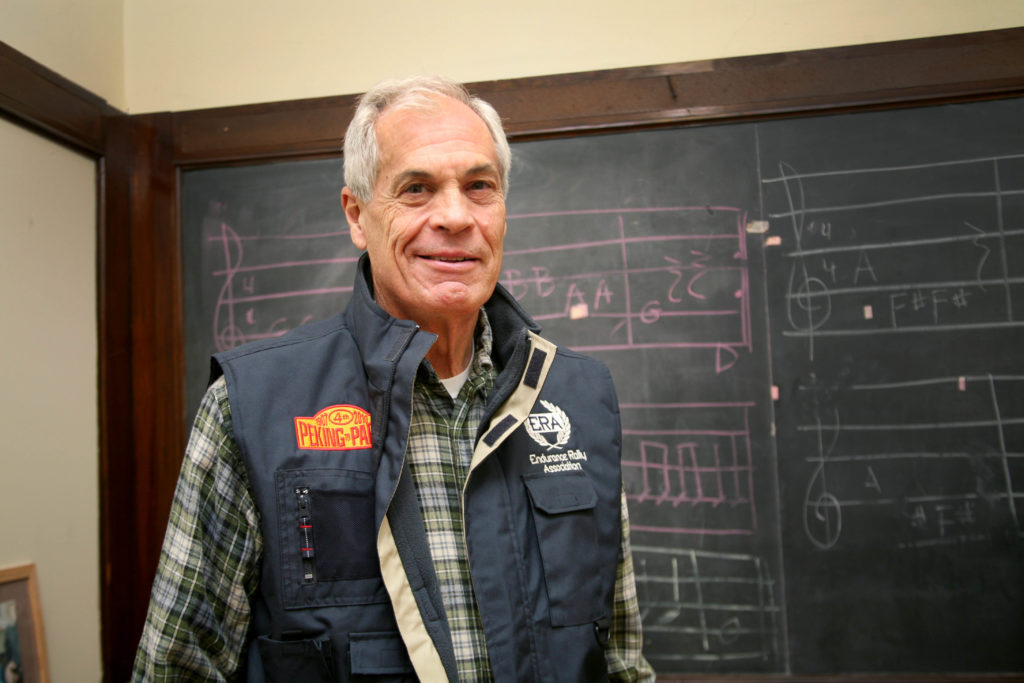

Lloyd is a tall man, somewhere around seventy, with short gray hair. He’s a great guy with a lot of stories to tell.

Rally driving isn’t something I get paid to do…it’s all about the challenge. One of the most memorable rallies I’ve done was the Peking to Paris rally, a thirty-seven-day-long endurance race across eleven countries starting in China, going through the Middle East, up through Turkey and Greece and into Italy and France. It’s perhaps the longest rally, and it’s done in old cars. It’s also a part of the world I wouldn’t have seen otherwise. I drove a 1949 Cadillac two-door sedan — a big, heavy car that I selected because it’s strong. I got it two and a half years before the rally, to prepare.

Usually during a rally, we all get up around seven in the morning, snag some breakfast, check the car, and get ready to go. Departure time depends on your car number. You wait your turn, and then you drive as fast as you possibly can. If you’re fortunate, you get to the next stop at five or six in the evening . . . although on some days, you get in later, and, one terrible night, we didn’t get in until past one in the morning.

My team helps me in a lot of ways. My navigator sits beside me in the car with the road book. He’s responsible for keeping all of the check-in materials, because in modern rallies, the cars have electronic tags to keep track of where they are. The other part of a team is the mechanical team. However, in the Peking to Paris rally we didn’t have a support team of our own. In that case, there were three mechanics and three trucks, and if you broke down, they couldn’t spend more than fifteen minutes on you. The most crucial part of the team, I’d say, is the people that prepare the car ahead of time. Sometimes it takes people years to prepare for a rally.

My favorite day of the Peking to Paris rally was probably the rest day I spent in Samarkand, which is a wonderful city. I worked on the car in the morning and then spent the rest of the day walking around. On the flip side, the worst day I’ve had was in Turkey. It had been snowing the night before and it was foggy and our time trials were on very slippery, muddy roads. We had more mud than you could deal with at one time.

The other bad day was the sheep incident. This was in Uzbekistan. We were driving along, and it was the first good stretch of road we’d had in days. It was actually a paved road, and in the center strip there was a whole herd of sheep. There was a hole in a fence on the side, and out came a sheep two hundred yards in front of me and I said, “Oh, this could be bad.” I blew my horn and all that did was produce more sheep. I slammed on the brakes and the car behind me was about to hit me, so I thought, “I’d rather hit a few sheep than be hit by a car.” At this point, there was no room for the car to pass me, so there was no other option. I turned to my navigator and said, “Chuck, we’re goin’ in. Brace yourself,” and then we hit two sheep. I wound up having to pay for two sheep and I didn’t even get to keep the sheep. That was a bad day.

I decided to do the rally because of the people I got to meet from the towns and cities along the way. And that’s the thing about rallies: they are a fun way to meet great people and travel to the ends of the earth. We spent seven days in the Gobi Desert during that race. You can go as a tourist, but there’s nothing like living in the desert. It’s an adventure. I’m not interested in driving rallies like the Colorado Grand, where there’s no timing and it’s just a tour, just driving an old car through the countryside. It’s gotta be competitive for me.

Back when the Peking to Paris rally first started, in 1907, cars were the play toys of the idle rich. They wanted to prove that one day the automobile could be used for long-distance travel. I’m currently looking at doing other rallies like a South American rally that goes from Rio de Janeiro across to Cuzco and then up to Machu Piccu and all the way south to Tierra del Fuego. Talk about long-distance travel! I’d like to keep doing this for as long as I can, hopefully without another sheep incident.

AUTHOR REFLECTION

Before I interviewed Lloyd, I didn’t even know you could do a rally if it wasn’t your job. I had intended to talk to someone who did this as their career, and because this wasn’t Lloyd’s actual job, I had to modify some of my questions for him. It was alright, though, because his stories still blew me away. The way he described his average day in the rally was astounding. I especially liked when he talked about the time he spent in Samarkand. I didn’t know where Samarkand was, let alone that it was built by a ruler with an empire twice the size of Genghis Khan’s.

Another thing that interested me was how far he was traveling in an old 1949 Cadillac. It had been beefed up for racing, but still a two-seater. He drove across eleven countries in thirty-seven days. I have trouble driving two and a half hours to Albany! Along the way, he met so many interesting people in so many interesting places.

My favorite part of the interview was definitely when Lloyd showed me pictures of the rallies. It allowed me to match the places to the stories and the faces to the people. I’m not completely sold on making a career out of racing; it’s risky to assume that you can make a living doing this. Maybe later in life, after I’ve gotten a job and had some experience in racing, I would try a rally like this. I think it would be great to travel like this, but not for a paycheck. I would do it for fun.

From Mayor Menino to a race car driver, these profiles and interviews written by middle school students at the Mission Hill School explore students' career aspirations. Each interview features a wood-cut illustration of the subject.

View In Store Read more from this book »